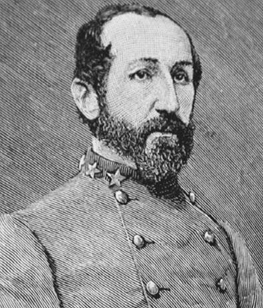

JOSIAH GORGAS

CHIEF OF ORDNANCE

The successful operation of the Richmond Arsenal for four long years of civil war is proof of what can be accomplished with leadership, enterprise and hard work by a people totally unprepared for war. When the war began, the South had no musket caps, no improved arms, no sabers or carbines, no powder, no powder mills, no cap machines, no improved cannon and no arsenals. Into this seemingly hopeless situation came Josiah Gorgas, a man with a genius for organization and a flexible mind that explored all possibilities to their utmost limits, talents that propelled him to the rank of Brigadier General in the Confederate Army. He had both the ideas and the force of leadership to provide the tools of war to a fledgling nation that had neither the raw materials nor the all-important know-how when the fighting began.

Gorgas (1818-1883) was born in Pennsylvania. He attended West Point where he graduated sixth in his class. Upon graduation in 1841, he was assigned to the Ordnance Department of the United States army. Josiah Gorgas’s first experience in the field was serving with General Scott in the Mexican War where he participated in the siege of Vera Cruz. Upon the conclusion of the war Gorgas was promoted and sent to the Mount Vernon Arsenal near Mobile, Alabama, where his life changed. While in Alabama he fell in love with, and married, a well-connected southern woman. His new life led to his support of the South during secession. Gorgas had been in the United States Army for 15 years at the outset of the war, and had served at the Frankfort Arsenal in Philadelphia, a stint that would prove invaluable.

A cool, aloof man who appeared perpetually irritated, Gorgas accomplished a near-impossible feat. Supplying ordnance was a difficult task, as was any other logistical endeavor in a South suffering from inflation and lack of official currency. With good reason the people resisted government promissory notes - there were no funds.

Although President Jefferson Davis was not personally acquainted with Gorgas, he nevertheless commissioned him chief of the Ordnance Bureau, solely on Gorgas' past record and the recommendations of others. Josiah Gorgas wrote in his journal that “on the 7th of April I reached Montgomery and on the 8th took charge of the Ordnance Bureau, being assigned to duty as Chief of Ordinance” (Wiggins 1995,149). In every possible way, Gorgas used his energy and ingenuity to supply the South. Domestic production was Gorgas' main hope and he worked to expand factories and shops. He also offered help to small businesses and was alert to encourage potential furnaces, mines and smelters.

His assignment as the Chief Ordnance officer for the Confederates proved an arduous task that tested his organizational abilities. In April, 1861, when Josiah Gorgas took over the Confederate Ordnance Department the South was without any means to create ammunition or powder. The Confederacy's supply of arms was dangerously low and manufacturing facilities almost nonexistent. Although Gorgas sent purchasing agents to Europe, no shipments were received before 1862. Despite the enormous difficulties, however, Gorgas built up the South's war machine and supplied munitions to the Confederate armies until the war's end.

At the same time, Gorgas vigorously pursued all avenues of blockade running. He wanted the government to be engaged in eluding blockaders in the same way that private enterprise was successfully managing to do. Gorgas was the first to suggest that the government own and operate ships to run the blockade. He bought the ships, found the cotton to be traded to foreign markets, and sent out agents who had previously succeeded at blockade running.

Within the Confederate States of America there was not so much as one arsenal or powder mill. This problem was compounded since the United States War Department years before the war reduced the supplies in the southern armories. Several actions taken by Josiah Gorgas allowed him to create an ordinance department from scratch.

"An excellent powder-mill was built at Augusta by one of his ablest subordinates, Col. George W. Rains. Lead was mined, under contract, near Wytheville, Va., a small amount of copper in East Tennessee, and iron chiefly in Virginia and Alabama. Saltpeter, used in making powder was imported or made from the nitrous earths of caves and artificial beds. In 1862, a separate mining bureau was organized under the direction of Col. Isaac M. St. John, who began the work under orders from Gorgas. Gorgas found it necessary to scatter his establishments over the country, because railway transportation was too weak to carry the raw materials to a central point. By 1863 he had the ordnance bureau operating with high efficiency.

The Richmond Arsenal was both a repository for arms and military stores and an establishment where arms and military supplies were manufactured. It was located in the industrial center of Richmond. It was here that the mills and factories were located: the arsenal, the armory, the Tredegar Iron Works and the laboratories.

Before the war, Richmond had been an important center for the United States Ordnance Department. Although the South was mainly rural, Richmond was a modern city. As the capital of a new nation at war, Richmond tripled its population in a few years' time and suffered critical food shortages and other problems as a result of the rapid growth and the war.

The arsenal was located at the foot of 7th Street, near the James River and the Richmond and Petersburg Railroad Bridge. By employing few hands but with improved machinery, the arsenal was prepared to make 300,000 caps per day. These caps, made with "wonderful rapidity," were tested and found to be superior to English-manufactured caps.

The scrap metal left from the manufacture of caps was ingeniously converted by a Virginia mechanic into an alloy that could be worked and re-worked until it was all used.

Few men were employed at the arsenal; the majority of the work was done by women and children. And the work was dangerous. On March 13, 1863, an explosion rocked the Confederate States Laboratory on Brown's Island, located not far from the arsenal, killing 45 women and children. The employees of the arsenal gave generously to a committee formed by the Young Men's Christian Association to relieve the suffering of the injured and their families.

The Confederacy also was able to construct powder mills it felt were the equal of any in the world. For example, when the scarcity of copper began to be felt because the North had gained possession of such mines in Tennessee, the South mined the pure copper from North Carolina and elsewhere and used the copper from turpentine and apple brandy stills. Thus the South was able to purchase and otherwise secure enough copper, although because of the blockade they could not rely on foreign suppliers.

An extraordinary amount of energy and enterprise was used to convert the stills for daily use. The stills were cut to pieces, rerolled and handed over to the cap manufacturer. The armies of the Confederacy, during the last 12 months of the war, used caps manufactured from North Carolina stills.

When copper ceased to be available for casting Napoleon guns, a light, cast iron-banded, 12-pounder gun was substituted. According to reports, this gun was believed to be superior in range and durability to the bronze Napoleon gun.

After the Federals had captured the copper mines of Tennessee, the scarcity of copper caused the South to suspend the casting of bronze fieldpieces and to hoard the existing copper for use in the manufacture of percussion caps. A simple and excellent machine for making, filling, pressing and varnishing caps was invented, patented and used with success. It took eight people to operate the machine - two men, and six boys and girls, to complete over 300,000 caps - stamping, filling, pressing and varnishing within eight hours.

For the completion of these machines, the Confederate government awarded the sum of $125,000, which was about $2,000 in gold.

The Richmond Arsenal operated so successfully that the issues from the arsenal represented approximately half the total issues used by the Confederate Army. Fieldpieces of all descriptions were classed among the issues, including all those pieces obtained by manufacture, purchase or capture and afterward issued from the arsenal. The infantry arms issued included the arms manufactured at the Confederate States Armory, those obtained by purchase or capture, and those turned over to the Confederate States Arsenal by the state of Virginia.

Assuming that 100,000 Federals were killed in battle, not counting wounded or those who died from disease, it has been estimated that 150 pounds of lead and 350 of iron were fired for every man killed; if the proportion of killed to wounded is one to six, it would further appear that one man was disabled for every 200 rounds expended.

In former wars, with the old smoothbore musket, it was generally said that "his weight in lead is required for every man who is slain." From the above statistics, it does not appear that the rifled musket was any improvement.

The Confederate government, through its officers, traditionally has been held responsible for the destruction of the city of Richmond on the morning of April 3, 1865, including the burning of the arsenal. However, Richmond resident W. LeRoy Brown gave this account in 1869: "Between five and six o'clock on the morning of April 3, 1865, the commanding officer visited every building, had the gas extinguished and instructed the guards to shoot down any man who attempted to fire a building. It was only an hour later rapid explosions of shells heard in the distance convinced him that the arsenal was being destroyed by the torch of an arsonist or a frantic mob."

When Petersburg fell on April 2, Richmond was evacuated by the Confederates, who set fire to the business district, bridges, military stores and tobacco warehouses. Before the fire could be extinguished by Northern soldiers, one-third of the city was burned. The fire burning this part of Richmond silenced the busy whirl of machinery, the metallic sounds of the hammers, and the voices of men, women and children working in the desperate last hours of a nation at war.

At the time of the evacuation of Richmond, there were probably about 25,000 rounds of artillery ammunition, mostly for siege guns, in the storehouses of the arsenal. During the Sunday night of the evacuation, an attempt was made to destroy the ammunition by throwing it in the river. This was soon abandoned as there was not enough manpower for the job. Several canal boats were filled with the most valuable cap machinery and small arms and ordered to Lynchburg. It was the end of four years of successful operation by the arsenal.

When the war began, the arsenal workers were untrained, unskilled, awkward apprentices-three years of patriotic toil turned them into excellent workmen. They took pride in the fact that no battle had been lost by the Confederate armies for want of ammunition.

By the close of the war Josiah Gorgas was able to supply the Confederate Army with more-than-sufficient amounts of gunpowder and ammunition. In a rare expression of self-satisfaction, Gorgas once boasted: "I have succeeded beyond my utmost expectations. From being the worse supplied of the Bureaus of the War Department it [Ordnance Department] is the best." He went on to mention specifically the Richmond Arsenal. The successful operation of the arsenal was greatly due to his ability to meet the demands of economy and necessity with ingenuity and simplicity.

After the war, Gorgas taught at the University of the South, at Sewanee, Tenn., and was made president of the University of Alabama in 1878, where he remained until he was compelled to resign owing to failing health. He died in Tuscaloosa, in May 1883.

References:

• Wikipedia.org

• http://www.knowsouthernhistory.net

|