The

young drummer beat the call to assembly, and the gray-uniformed

cadets fell into ranks on the color line. Instead of weapons the

boys carried schoolbooks, and they assembled not into military

companies, but into class details. All present or accounted for,

they marched to their respective classrooms. It was Monday, April

3, 1865—time for two o’clock classes at the University

of Alabama, for the past five years the state’s military

school.

One section, commanded by cadet Captain W.H. Ross, made its way across

campus to the residence of John W. Pratt, professor of logic, oratory,

and rhetoric. The students entered the classroom on the lower floor,

and after the group had been seated, Ross, serving as spokesman, pled

their case. The week before, he reminded Pratt, the Corps of Cadets had

been called out and marched across the Black Warrior River bridge and

several miles beyond Northport in an attempt to intercept a group of

Federal cavalry rumored to be swooping down on Tuscaloosa. The cadets

had thrown out pickets and awaited news of the raiders, but had heard

or seen nothing. Two days later, on Saturday evening, when the officer

commanding the expedition determined that the danger had passed, the

Corps marched back to the campus. Because of these operations, Ross pointed

out, members of the class had had no opportunity to prepare their rhetoric

assignments, and he asked that they not be graded on the day’s

lesson.

Landon C. Garland (1810-1895), a Virginian, spent sixty-four

years in Southern higher education. As president of the University

of Alabama, he turned the institution into the state’s

military academy. “He seemed to gain obedience and respect

through the love and affection the boys and young men felt

for him,” Benjamin M. Robinson, a former cadet, recalled. “It

was this gentleness and tolerance and understanding of young

men…that endeared him so greatly.” In 1867 Garland

accepted the chair of physics and astronomy at the University

of Mississippi, and in 1875 he was made chancellor of Vanderbilt

University. Garland was photographed at Mathew Brady’s

Washington Gallery in 1860 wearing his new uniform as superintendent

of the Alabama Corps of Cadets. |

Pratt certainly

understood the cadets’ plight. Rumors of Union raids had

kept the University stirred up throughout the spring, and the

Corps had been called out several times before. He forgave the

class its lesson for the day and permitted the students to spend

the time discussing the current state of military affairs. When

the period was nearly over, Pratt assured the young men that

there was not a Yankee within fifty miles of the campus, and

he urged them to pay less attention to the incessant rumors and

to pursue their studies more diligently. With that pronouncement,

the boys left to answer the next call of the drum.

The students

had reason to be concerned about Federal raiders. A Union force

threatened Mobile, while yet another controlled Alabama north

of the Tennessee River. Southern defensive forces were few. The

Army of Tennessee had been shattered at the battles of Franklin

and Nashville, and the only major Confederate force left to meet

a threat to central Alabama was Lieutenant General Nathan Bedford

Forrest’s cavalry.

Further, as

Confederate authorities were aware, a large force of Union troops

under Major

General James H. Wilson had left its camp on the Tennessee River

in northwest Alabama and was moving south, threatening the central

part of the state.

On March 30, Wilson reached the village of Elyton (now Birmingham). Here

he ordered Brigadier General John T. Croxton to lead his 1,500 seasoned

cavalrymen, armed with Spencer repeating rifles, on a side expedition

designed to divert Forrest’s attention. Croxton’s orders

were “to proceed rapidly by the most direct route to Tuscaloosa

to destroy the bridge, factories, mills, university (military school),

and whatever else may be of benefit to the rebel cause.”

Croxton lost no time, leaving that afternoon for Tuscaloosa, only fifty

miles away. But an encounter with Confederate Brigadier General W.J.

Jackson delayed him and changed his intended route [see “The Approach

to Tuscaloosa”], and it was not until Monday, April 3, that Croxton’s

cavalrymen finally found themselves north of the Black Warrior River

on an unopposed approach to Tuscaloosa.

On Monday, April 3, 1865, the cadets at the University followed their

normal school-day routine—a strict regimen that dictated their

movements from wake-up to lights out. They dressed and answered the call

of the long roll at six o’clock. After roll call, they prepared

their rooms for the day and studied until time for prayers at seven,

followed by breakfast. At eight o’clock, classes began and ran

until one, when the midday meal was served. The afternoon included classes

from two to four o’clock, when the cadets formed for an hour of

drill. The next hour was free. Supper was from six to six forty-five,

followed by forty-five minutes of free time. The two hours from half

past seven to half past nine were given over to study, followed by preparation

for lights out, which came at ten o’clock.

Cadet Greene Marshall Labuzan* from Mobile entered the

University of Alabama in 1863 at the age of seventeen. Labuzan,

who later became a successful attorney, took command of the

skirmishers after John H. Murfee was wounded. |

The University

had not always been so orderly. Opened in 1831 and modeled on

universities in the more settled states to the east, the institution

had been founded to provide a classical education to the state’s

youth and to prepare them for service to church, state, and society.

But in the young state of Alabama, ideals of scholarship and

strict codes of conduct had met head on with the realities of

frontier education. The sons of Alabama’s pioneers were

accustomed to doing as they pleased, and early on the boys discovered

that the University’s regulations could be disobeyed with

impunity.

Despite the best efforts of the University’s first two presidents,

Alva Woods and Basil Manly, University students continued to play fast

and loose with the rules, often sneaking from their rooms at night to

go to town. Drinking, gambling, and general rowdiness prevented many

from attending to their studies, and the situation did not improve over

the years. Indeed, in 1857, one student killed another student in a gunfight.

Something had to be done.

Landon C. Garland, president of the University since 1855, believed that

the answer to student discipline problems lay in a military system, and

for the next five years he urged the state legislature and the University’s

board of trustees to implement such a system. Finally, on February 23,

1860, with tensions mounting between North and South, the legislature

acceded to Garland’s demands.

In a rush to prepare for the start of the new session, Garland traveled

north, visiting other military schools, including the Virginia Military

Institute and the United States Military Academy at West Point. He placed

orders for uniforms, arms, and other equipment, and acquired the services

of a regular army officer, First Lieutenant Caleb Huse, who was granted

a leave of absence by the War Department to accept appointment as the

University’s first commandant of cadets. With his preparations

completed, Garland opened the 1860 fall session on time.

Although many

of the faculty were initially skeptical of the benefits of a

military system, none could ignore the marked improvement in

student discipline that accompanied the introduction of the system.

Within a month of the start of the session, students showed evidence

of better study habits, discipline, and even better health.

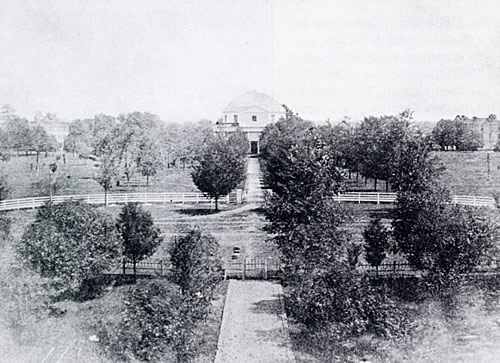

The Rotunda of the University of Alabama, designed by William Nichols,

was completed in 1831. Seventy feet in diameter and seventy feet

in height, the structure formed the nucleus of the original campus.

The only known photograph of the Rotunda was taken about 1859. |

But the new

system proved expensive. In an effort to win an additional appropriation

from the legislature, President Garland conceived a daring public

relations move: He and Commandant Huse would take the Corps of

Cadets to Montgomery, where they would be reviewed by the governor

and the general assembly. Against the advice of some members

of the faculty, who feared that the young boys would not be able

to resist the temptations incident to such a venture, the cadets

traveled to Montgomery in January 1861.

From the moment of their arrival in Montgomery aboard the double-decked

riverboat Southern Republic, the cadets captured the imagination

of the citizenry and became the darlings of the city. During their five-day

stay, they won compliments for their sharpness and precision at drill,

as well as for their gentlemanly behavior. The legislature responded

as Garland had hoped and unanimously passed an act to increase the University’s

funding.

Within months of the trip, the Civil War began, and many of the cadets

were called upon to drill troops in other parts of the state. Some joined

the regiments they helped train; others, in their rush to see service,

left to join companies being formed in their own home towns. During the

next four years, many students left before graduating, much to President

Garland’s disappointment. In fact, in 1862 so many students left

that there was no graduating class. Yet there were always more applicants

for admission to the University than places for them, even after additional

dormitories were built in 1863, allowing the Corps to expand from 200

to 300 cadets.

Those students who remained at the University found themselves assigned

to various duties in addition to their studies. They guarded wagonloads

of supplies en route through lawless areas, and on several occasions

members of the Corps engaged the enemy, most notably on July 18, 1864,

when University of Alabama cadets were part of a force which met and

turned away a Federal raid into east Alabama. Part of the winter of 1864-65

the cadets spent in Mobile, bolstering the defenses of that city.

Throughout the war the University supplied the Confederacy with a cadre

of young men with military training. In President Garland's own words, "We

annually send about 200 youth, well drilled in infantry and artillery,

into the field." It is no wonder that the University became known

as the "West Point of the Confederacy."

Throughout

the day of April 3, Croxton and his 1,500 cavalrymen

moved down Watermelon

Road toward the Northport-Tuscaloosa bridge. About dusk they

reached North River, which flows into the Black Warrior River

about five

miles from Tuscaloosa. Delayed briefly by shots fired at them

from ambush, they crossed the river and rode through the dark

until about nine o’clock, when they reached the eastern

outskirts of Northport, directly across the Black Warrior from

Tuscaloosa.

André Deloffre, librarian and professor of French,

attempted to save the University of Alabama library from destruction

in 1865. Deloffre, who came to the University in 1855, sometimes

surprised his associates. It was said that a member of the

military faculty once picked up a sword and jokingly challenged

Deloffre. “The old man’s eyes sparkled; and, quick

as a thought, he snatched up a sword and in a few passes knocked

the sword from his antagonist’s hand and ran him back

into a corner of the room, to the great amusement of the crowd.” It

seems that the professor had been a French soldier during the

Revolution of 1848. Soon after the Civil War ended, Deloffre

moved to Mobile, where he continued to teach French until at

least 1875. It is believed that he returned to France. |

The Black Warrior

River that Croxton prepared to cross bore little resemblance

to the deep, navigable river of today, for Tuscaloosa was situated

on the fall line of the river, and steamboat travel ended there.

Stretching from bank to bank were the Falls of the Black Warrior,

whose sounds could be heard much of the time by the residents

of both towns. Rising from these shoals were brick pillars supporting

a covered bridge.

On the night of April 3, the bridge was guarded by a detachment of the

home guard, commanded by Captian B.F. Eddins, a retired Confederate officer.

Sentinels guarded the north end of the span, while the main guard, protected

by cotton bales, occupied the center of the bridge.

Croxton’s plan of attack called for 150 unmounted cavalrymen to

move as close as possible to the bridge and wait for dawn, when they

would rush the bridge and secure it for the rest of the brigade, who

were to dash across on horseback and envelop the city. When Croxton heard

the Confederate home guard removing the flooring from the bridge, however,

he decided to act more quickly: He sent ahead two volunteers and a black

guide to reconnoiter. Divesting themselves of their equipment (except

for their revolvers), the three started for the bridge.

When the reconnoitering party was about thirty feet from the bridge entrance,

a member of the home guard stepped out to challenge them. One of the

Federal volunteers, Private Charles Wooster of Michigan, recalled what

happened next:

As he

steps out into the light he looks down on us and quickly

challenges: “Who’s there?” “Friends!” I

reply, but he couldn’t “see it,” and instantly

fired; the ball passed through the crown of my hat, and he

beat a hasty retreat through the bridge, followed by our

balls; as our support was up the bridge was cleared, and

the man who first fired on us left mortally wounded near

its center;—there were 14 rebels in the bridge, in

all.

The fight

had been brief. The Federals quickly relaid the twenty feet of

the bridge flooring that the home guard had removed and crossed

into Tuscaloosa. Parties of horsemen spread out searching for

selected targets and Confederates who might be about.

At

the University, about a mile upriver, the first guard tour of

the evening was nearing its end. Shortly before eleven o’clock,

cadet Sergeant J.G. Cowan. Cowan dressed quickly and posted his

guard detail. The night was dark

and

rainy, and Cowan settled down in the guardhouse to finish preparing

his next day’s assignments. The University musicians, slaves

hired for their skills with drum and fife, slept in their accustomed

places on the guardhouse floor.

Around midnight, a rider from town approached the President’s Mansion.

Moments later President Garland ran across the campus from his home,

crying “Beat the long roll! The Yankees are in town!”

Professor John W. Pratt, a faculty member at the University

of Alabama during the Civil War, was renowned as a teacher.

A former student recounted how he had made his lowest grade

in Pratt’s class. One of the questions on a logic exam

was, “What is the probability of throwing an ace in three

throws of dice, expressed in fractional terms?” The student

answered that he did not understand the question. Later, he

admitted that he did not know what dice were. Pratt replied, “You

ought to have a zero for being too proud to ask for information,

and a hundred for not knowing how to play dice.” In his

later years, Pratt became president of Central University in

Richmond, Kentucky. |

Cowan immediately

roused the musicians, Neil, Gabe, and Crawford, from their pallets,

and within moments the air was filled with the sonorous rattle

of the drums. Sleepy-eyed boys, who had been in bed only two

hours, hastily dressed in the dark, grabbed their belts, cartridge

boxes, and muskets, and ran down the stairs and into the darkness,

where they assembled in company formations.

Commandant

James T. Murfee assumed command. (Murfee had replaced Caleb Huse

in 1861, when Jefferson Davis sent Huse abroad to buy arms for

the Confederacy.) Murfee ordered his brother, Captain John H.

Murfee, instructor of tactics, to deploy one platoon of Company

C as skirmishers. Their mission: to proceed toward town, locate

the enemy, and determine his strengths and weaknesses.

Through a thin, misty rain the boys advanced in open formation, nervously

peering into the darkness not knowing the location of the enemy. As the

boys entered town they moved closer together, regaining their ranks and

files.

When Captain Murfee and his cadets reached the town center, Murfee, intending

to turn the platoon onto the street leading downhill to the bridge, gave

the command, “Right wheel—forward march!”

Almost immediately a challenge rang out of the darkness only a few yards

from them. “Who comes there?”

“Halt!” Murfee cried out, stopping the turn. Then he replied, “Cadets!”

“What regiment do you belong to?” came the reply.

“Alabama Corps of Cadets,” answered Murfee.

“Let them have it boys,” said the answering voice, and immediately

the Federal pickets opened fire.

“Fire and load lying—lie down,” called out Captain Murfee,

though most of his detachment had anticipated him. After a few rounds of firing,

during which Murfee and two cadets were slightly wounded, the Federal pickets

turned and ran. Soon the night was still, the silence broken only by the murmur

of the Falls of the Black Warrior.

The

remainder of the Corps had followed the skirmishers down the

road into town. Guarding the formation’s right on that

march was a small detail consisting of Captain John Massey, Professor

W. J. Vaughn, and Paul Tricou, the University bookkeeper, who

proceeded down a parallel street closer to the river. On their

way, they passed the home of Dr. S. J. Leach, where a wedding

had taken place earlier in the evening (see story), but they

encountered no one until they rejoined the rest of the Corps

at the top of River Hill.

Another detail of cadets proceeded to Baird & Hunt’s Livery

Stable in downtown Tuscaloosa with orders to bring up the three fieldpieces

belonging to the Corps. Ordinarily, these cannon would have been kept

at the University, but the post commander at Tuscaloosa had turned them

over to an artillery officer the week before, when the Corps had been

called out to guard the city. When the force returned on Saturday, the

guns had been placed in the livery stable. Now they were gone. Croxton’s

men had gotten to them first.

Cadet Edward Nicholas Cobbs Snow (1845-1926), from Tuscaloosa,

was with the Alabama Corps of Cadets in 1865, when the University

of Alabama was burned. Snow is pictured in his full-dress cadet

uniform. |

When

the firing began on River Hill, the main body of the Corps, under

Commandant Murfee, had just entered the city limits. Hearing

the gunfire, Murfee ordered the Corps forward at the double quick,

halting it briefly about a half block short of the street leading

to the bridge. Murfee positioned the Corps in line across the

top of River Hill, facing the bridge, and sent a platoon from

Company B, under cadet Captain Samuel Will John, to take position

a block closer to the river on the street immediately to the

west.

Meanwhile, Captain Murfee and his skirmishers rejoined the main body

of the Corps, and the wounded—including Murfee and cadets W. M.

King and W. R. May—were carried to places of safety. Cadet A. T.

Kendrick was slightly wounded but remained with the Corps.

For several minutes there was silence. Then Captain Massey and two cadets

went forward to reconnoiter. They had gone perhaps two hundred feet downhill

when they were challenged.

“Who

goes there?” came out of the darkness in an Irish brogue.

“A Rebel,” came the clear reply, followed by the cocking of the enemies’ guns.

The Federals fired their Spencer repeaters blindly into the night, hitting no

one, and the Corps of Cadets, situated at the top of the hill, fired several

volleys in return. In a short while the firing ceased, and the reconnoitering

party, uninjured, rejoined the main body of the Corps at the top of the hill.

Jefferson Elisha Bozeman (1844-1897), from Autauga County,

entered the University in 1862 and was one of the cadets who

met Croxton’s forces on River Hill. He later served as

a state representative. |

As the Corps

waited in position, President Garland held a conference with

Commandant Murfee and Captain James S. Carpenter, a Confederate

officer [see “Bridesmaids and Bullets: A Melodrama”].

Carpenter informed Garland and Murfee of the overwhelming odds

facing the small force of three hundred boys. Not only were the

cadets outnumbered, but the Federal troops were armed with repeating

rifles. And to rub salt into the wound, the Corps’ own

fieldpieces, captured before they could be brought into play,

were now trained on the bridge and its approaches from the Northport

side.

Garland made his decision. Unwilling to commit the Corps to useless sacrifice,

he marched the boys back to the campus. Once there, they quickly gathered

their overcoats, blankets, and haversacks, which they filled with hardtack

from the commissary stores, and fell back into ranks.

By two o’clock in the morning the Corps and many of the faculty

were marching east along the Huntsville Road, away from Tuscaloosa and

the University. About eight miles from town, the Corps crossed the Hurricane

Creek bridge and, once on the other side, pried up the bridge floor and

entrenched themselves on a hilltop to the east. That done, they settled

in to wait, wondering if the Union cavalry would pursue them.

James Thomas Murfee (1833-1912), commandant of cadets at

the University of Alabama, was in command during the Federal

raid of April 3-4, 1865. Following the war, he remained at

the University and served as architect for the new campus,

which consisted solely of the “University Building,” later

named Woods Hall. In 1871, Murfee accepted the presidency of

Howard College and more than a decade later he founded Marion

Military Institute. |

Morning,

April 4, found General Croxton in peaceful possession of Tuscaloosa,

but his mission was not yet completed. Under orders from Croxton,

Colonel Thomas M. Johnston of the Second Michigan Cavalry led

two hundred men east on Broad Street and out the Huntsville Road.

About a mile from town on the left, Johnston and his men spotted

the wooden fence enclosing the University grounds. Across the

way, visible through the spring-green trees, were the University

buildings. To the soldiers’ right stood the President’s

Mansion, an imposing, Greek revival structure, surrounded by

fields. The blue-coated column wheeled left, passing through

a wooden gate onto the tree-lined, gravel road leading through

the campus. Before them stood the University of Alabama as it

would never be again.

In the center

of the campus and immediately in front of the approaching Federals,

about eighty-five yards away from the main road, stood the Rotunda,

home of the University’s library and natural history collection.

Standing in front of the Rotunda were several members of the

faculty, including André Deloffre, University librarian

and professor of French and Spanish, and Dr. William S. Wyman,

professor of Latin and Greek. Colonel Johnston, mounted on a

white horse (it was said he sat stiffly), approached the group

and made his purpose known. The University was to be burned.

Librarian Deloffre pleaded for the library. Surely this one building

could be spared. Colonel Johnston agreed that it would be senseless destruction

to burn one of the finest libraries in the South. Hurriedly he scrawled

a message to General Croxton asking permission to spare the building,

noting that it had no military value. No record exists of the conversation

between Johnston and the professors as they waited for a reply, though

Dr. Wyman later described Johnston as a “man of culture and literary

taste.”

When at last the courier returned, the general’s answer was disheartening. “My

orders leave me no discretion,” wrote Croxton. “My orders

are to destroy all public buildings.”

What happened

next has become a part of the University of Alabama’s mythic

fabric. It is said that Colonel Johnston, lamenting the destruction

of such a fine library, decided to salvage one volume as a memento.

Perhaps he sent one of his aides, or perhaps he sent Librarian

Deloffre, or perhaps he went himself, to take one book from the

library. The book saved was an English translation of The

Koran: Commonly Called The Alcoran Of Mohammed, published

in Philadelphia in 1853.

The Rotunda ruins were sketched in 1866 by Eugene Allen

Smith, former cadet and instructor of tactics. |

Federal troops then began throwing flaming combustibles through the open

door of the Rotunda and onto the roof. In a matter of minutes, the building

was engulfed in flames. The raiders then turned their attention to the

other buildings, and soon almost the entire campus was ablaze. One witness

recalled years later that “as I looked in astonishment, the flames

from the tall buildings reached far above the tree tops.” The University

cadets, from their position on Hurricane Creek, eight miles away, could

see the billowing smoke.

In addition to burning the University, Croxton’s men also burned

properties in and near town, including the Confederate nitre works, the

Leach & Avery foundry, a hat factory, a cotton mill, a tanyard, and

two cotton warehouses.

Brigadier General John T. Croxton (1837-1874), who led

the raid on the University of Alabama, resigned from the army

at the end of 1865 and returned to his native Kentucky to practice

law. Though suffering from Tuberculosis, he accepted an appointment

in December 1872 as U.S. consul to Bolivia, where he died two

years later at the age of thirty-six. (Courtesy Library of

Congress.) |

The next day,

April 5, Croxton and his troops left town, crossing the Black

Warrior River and burning the bridge behind them. They headed

west on the Columbus Road. At Romulus, they encountered Confederate

Brigadier General Wirt Adams, whose force drove the Federals

back to Northport. Eventually, Croxton and his men made their

way across the state to rejoin General Wilson in Georgia.

The Alabama Corps of Cadets stayed at Hurricane Creek a full day before

marching sixty-seven miles to Marion, Alabama. There they learned of

the fall of Selma, which had occurred on April 2. Because the town of

Marion could not feed 300 boys indefinitely, the officers disbanded the

Corps with the intention of assembling again in thirty days. The Alabama

Corps of 1864-65, of course, never reassembled. On April 9, 1865, Robert

E. Lee surrendered to Ulysses S. Grant at Appomattox Court House, Virginia.

The Civil War was over.

Because the University of Alabama was destroyed so near the end of the

war, one can easily imagine a scenario in which the University survived

unscathed. Indeed, on the day following the burning, General Grant, several

hundred miles away, told General Sherman, “Rebel armies are now

the only strategic points to strike at.” But the University did

not escape unscathed, and the events of April 3-4, 1865, set back the

course of higher education in Alabama for decades. With no dormitories,

classroom, or public buildings, little money, and no library, the University

of Alabama started over.

*In the original printing of this article, we identified this soldier as “George C. Labuzan.” Many

thanks to Laurel Labuzan for providing the correct name.

|